Questioning the Revolution. The neo-Dadaist art of Pablo Echaurren

[ad_1]

Subverting the bourgeois world, overturning the civilization of capitalism, inaugurating a libertarian and po(i)ethical conscience. “Transvaluation of all values”, à la Nietzsche. These are the cornerstones of the metapolitical trace underlying the artistic work of Pablo Echaurren, an Italian visionary of Chilean origin. This is the indispensable premise for his Lusitanian exhibition “La Révolution. RSVP”, recently inaugurated at the Zé dos Bois gallery in Lisbon.

Metropolitan Indians

The exhibition anthologizes the works created by the artist in the late 1970s, at the time of his participation in the wave of counter-culture that swept over the Western world and in Italy manifested itself, among others, in the group of Metropolitan Indians. Youth political movement radically critical of the Western System, within it germinated the seeds of a “different” protest compared to that of ’68: the economic question, the political-social urgency and the ideological gaze were radically subordinated, if not rejected, to the urgency of artistic disorientation. The “call to arms” intercepted a neo-Dadaist and situationist sensibility (well documented by the fanzine “Oask?!”): the totalitarian oppression of the technocratic state had to be contested at its root – a cultural, anthropological and perceptive (i.e. aesthetic), even before ideological foundation.

The nonsense

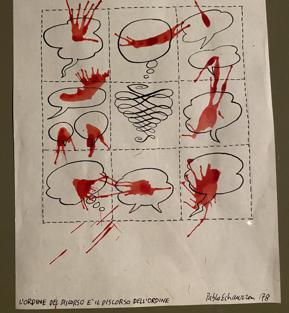

Creativity to unfold as a “flow of desire”, an instrument of existential enrichment, a collective drive towards change, was the lifeblood of neo-Dada anarchy. Here, in Echaurren’s art, a path is manifested along the path of an undermining of the logocentric principle, from which, in recent centuries, that reductionist, dualistic and analytical order, creator of conflicts rather than synthesis, has germinated. The non-sense that dadaistically pervades the colorful canvases on display in the exhibition becomes a celebration of the spontaneous wonder that the artist-child experiences by dancing between colors and brushes, enjoying the rhythm of that eternal return in which all rationalistic planning ultimately fades away. Likewise, other artistic series as original as they are conceptual intervene: among them, the ironic – and iconic – “small squares”, in which the images make explicit witty word games, with surrealist incursions; but also the collages and drawings made from 1977-78, in which the American Indians rise to symbols of a linguistic change and a disruption of the art market system. The gestures of détournement flash, the revival of the Duchampian ready-made, the unhinging of the usual use of terms, the performative dynamics of the word that becomes art, the overcoming of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture – an inclusive way to bring art into those worlds that the official system has always snubbed.

But has this mission finally been fulfilled? In Echaurren’s works one breathes celebration, a(nta)gonism, vitality, wit. By contrast, one can also grasp the political-cultural failure of an experience such as that of the Metropolitan Indians which, in its non-systematic nature, has failed to become a hegemonic culture, but, above all, has invested more in deconstruction than in reconstruction. So much so that today many stylistic features of the protest, as is known, the System has made them its own – rare, luxury goods, to arouse a “rebel”, but incapacitating aesthetic.

Is it possible – we ask ourselves – to found an ethic of aesthetics through works in which the tragic tension towards beauty has given way to the fragmentation of the image and to playful irony? Can nihilism, deployed in nonsense, really be the germinal source of a new existential horizon? These are questions that Echaurren himself certainly asked himself. Emerging also in some stages of his later production; particularly incisive, in this regard, the “artistic” comics in which he narrated the adventurous lives of some great illegal immigrants of the twentieth century: from Vladimir Majakovskij to Dino Campana, passing through Julius Evola, Ezra Pound and the much loved Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, to bear witness to the avant-garde of tradition and the overcoming of barriers – disciplinary, technical, ideological. In short, comics as an exercise in experimentation and cultural dissemination. A path that Echaurren has elaborated in particular in the careful and empathic study aimed at Futurism, of which, together with his wife Claudia Salaris, he owns the most complete collection in the world of magazines, flyers and posters.

[ad_2]

Source link